How green are investments in energy projects of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)? And in this context, what role do China’s arbitration courts play in the New Silk Road?

A green Silk Road was not only pledged by Jin Liqun at the foundation of the first Chinese dominated multilateral investment bank AIIB, but also by the Chinese government, when in May 2017, it promised hundreds of billions of $ US funding for investments by banks and companies along the New Silk Road. And even before the Paris Climate Agreement in November 2015, a green Silk Road fund to finance the “Green BRI” had been established in March 2015.

In their 2018 study “Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions”, the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the Global Development Policy Center (GDPC) have taken a closer look at the financial investments of Chinese development and investment banks. They discovered the following: between 2014 and 2017, six large banks – China Development Bank (CDB), Export-Import Bank of China (China EXIM) and the so-called “Big Four” commercial state banks – have invested 143 billion US $ in the energy and transport sector of the BRI.

Almost three quarters of this sum went to the oil, coal and gas industry. In the same period of time, direct loans of 45 billion US $ from the CDB and the China EXIM flowed into energy projects in BRI countries, 40 % of which went to the fossil and above all the coal industry.

China steps in, where other lenders back off

China is however, the world’s largest investor in the renewable energy sector. Outside its own borders, it nevertheless invests heavily in coal: the environmental and human rights organization Urgewald found out that a total of 221 gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired capacity is planned, almost twice the amount India intends to install and more than Germany’s current capacity of 200 GW. Chinese investors are stepping in where others are withdrawing from coal funding. According to a report published in 2019 by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Chinese development and state banks, as well as companies, are financing more than a quarter of all planned coal capacities (or those under construction) outside China.

In addition, Urgewald’s data show Chinese banks have assumed the dominant role in financing coal plants around the world, as they have underwritten 69% of global investments for coal. In other words: they ensure that these coal investments pay off. The population of the target countries will benefit less – if at all: in many places, urgently needed environmental protection rules are lacking, or these are relaxed against the backdrop of Chinese investment. Large-scale investments in coal will prevent these countries’ development in the long term. Coal plants have an average service life of 40 years.

New coal-fired power plants in Bangladesh financed by China

Coal is the dirtiest source of energy! The respective national development plans often contradict quickly decided investment plans. Bangladesh, for example, has made agreements with India, China, Japan and other states to build 29 coal-fired power plants, 13 of which are to be financed by Chinese institutions. In December 2019, over 40 mainly Asian organizations addressed an appeal to Bangladesh’s Prime Minister, to match words with deeds regarding the “Planetary Emergency” proposed by the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF). 29 new coal power plants were not the correct reaction!

In Myanmar, in the same area from where the violent clashes in connection with the Letpadaung copper mine resounded round the world, a gold/copper prospecting license for an area as large as Singapore, has yet again been granted to a Chinese state firm (PanAust, belonging to the Guangdong Rising H.K. (Holding) Ltd). The Sagaing region already suffers intensely from massive environmental damage.

When Chinese heads of state soon realize - far too late - that their actions violate agreed NDCs (nationally determined contributions) or adopted development strategies and a renegotiation or termination is/must be considered, or that they are deep in debt or investment commitments can no longer be met, then all these issues are generally a case for the arbitration courts. Investments by Chinese firms in the energy infrastructure sector are in most cases associated with land seizure, displacement and massive invasion of the ecosystem. Conflicts are preprogrammed.

Convergence of trade and investment arbitration

Chinese companies and also the Chinese state have in the past not necessarily experienced positive results in the existing conflict-solving institutions – whether in the trade or investment arbitration, amongst other things in investor-state dispute settlements (ISDS) as part of international trade agreements. The 2019 political briefing paper “China’s International Commercial Courts for the ‘Belt and Road’: A gateway for Beijing’s bigger role in global rules setting”, not only described why and on what basis the new Chinese commercial tribunals were created in 2018. It also outlined to what extent they are integrated into a new kind of trade and investment arbitration convergence.

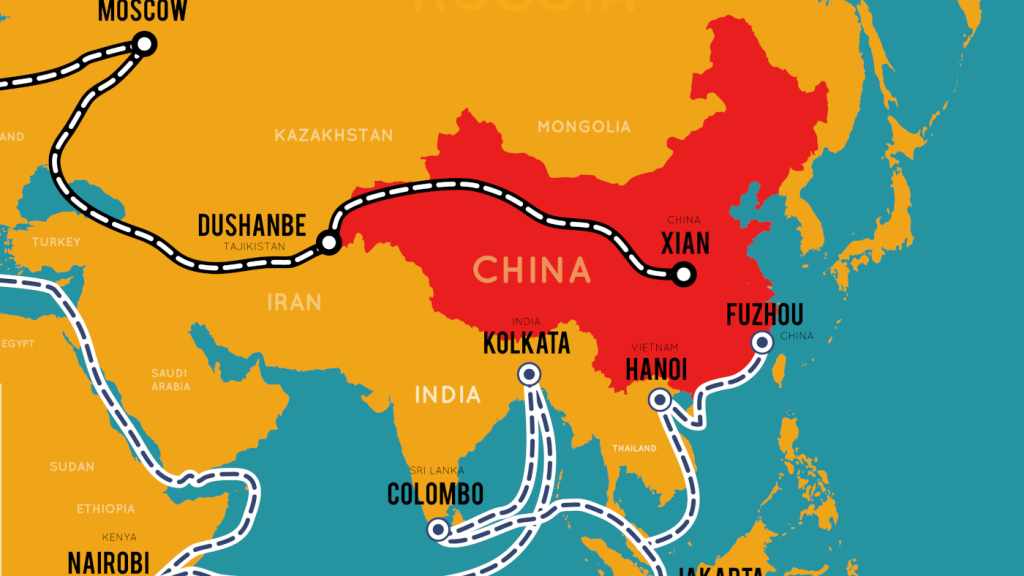

This is especially interesting, because the tediously negotiated investment protection agreement which was to be decided at the EU-China Summit and which has now been postponed to 2021 in Leipzig, is still pending. The new commercial courts in Xi’an (land route) and Shenzhen (maritime route) are specifically created institutions for the Silk Road, although they are not limited to them. However, in reality, they are only chambers beneath the Supreme People’s Court and thus part of the existing arbitration mechanisms, and are not authorized to deal with investor-state disputes, but as long as the EU-China Summit agreement is not yet decided, competence for investments within the BRI also remains unclear.

New arbitration courts: Chinese standards globally enforced

The new places of jurisdiction represent new “Legal Hubs” (Matthew Erie, 2019) that offer solutions from one single source and include jurisdiction, mediation and arbitration services. The latter are made available, inter alia, by the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) and the Beijing Arbitration Commission (BAC), both of which have recently published rules for arbitration between investors and states. The Shenzhen Court of International Arbitration (SCIA) has also recently expanded its rules, in order to meet the needs of arbitration between investors and states. This means the limitation to dealing solely with commercial disputes has been weakened, so that a future integration of investor and state disputes into the new courts could be made possible.

A large number of international cases have not yet been tried, but in December 2019, the courts demonstrated they could indeed take powerful action in order to globally enforce Chinese standards. One of their first decisions stated that the Italian manufacturer Bruschettini was to bear all costs of economic damage suffered by a Chinese importer after the import, sales ban and recall of a drug. A Chinese inspection team had discovered deficiencies in Italian production facilities.

The Silk Road courts will play a role for regional and international trade, especially against the background of the EU-China investment protection agreement. With regard to climate protection, the new courts will probably strengthen climate-damaging trade practice, because the states concerned – often China’s strategic partners and BRI supporters – will neither assert environmental laws aligned to the NDCs nor allow their inhabitants to take action against coal investments.